The Center for the Environment is an interdisciplinary hub of environmental research that is committed to generating transformative solutions to our deepest societal challenges including: climate change, air pollution, access to clean water, food insecurity, biodiversity loss and infectious diseases.

By the numbers

86

Center scholars

6

Teams/Grants supported

250+

Activity participants

208

Journal articles published in 2023

The Center’s mission

The center serves as a cross-cutting collaboration hub, encouraging partners, faculty and students to advance research projects in areas including biodiversity, environmental justice, planetary health, environmental solutions, and climate change. Here’s a closer look at who we are, what we do, and why it matters for our community, our region and our world.

Featured research & stories

Transforming wood waste for sustainable manufacturing

Foston takes detailed look at lignin disassembly on path to replace petroleum with renewables

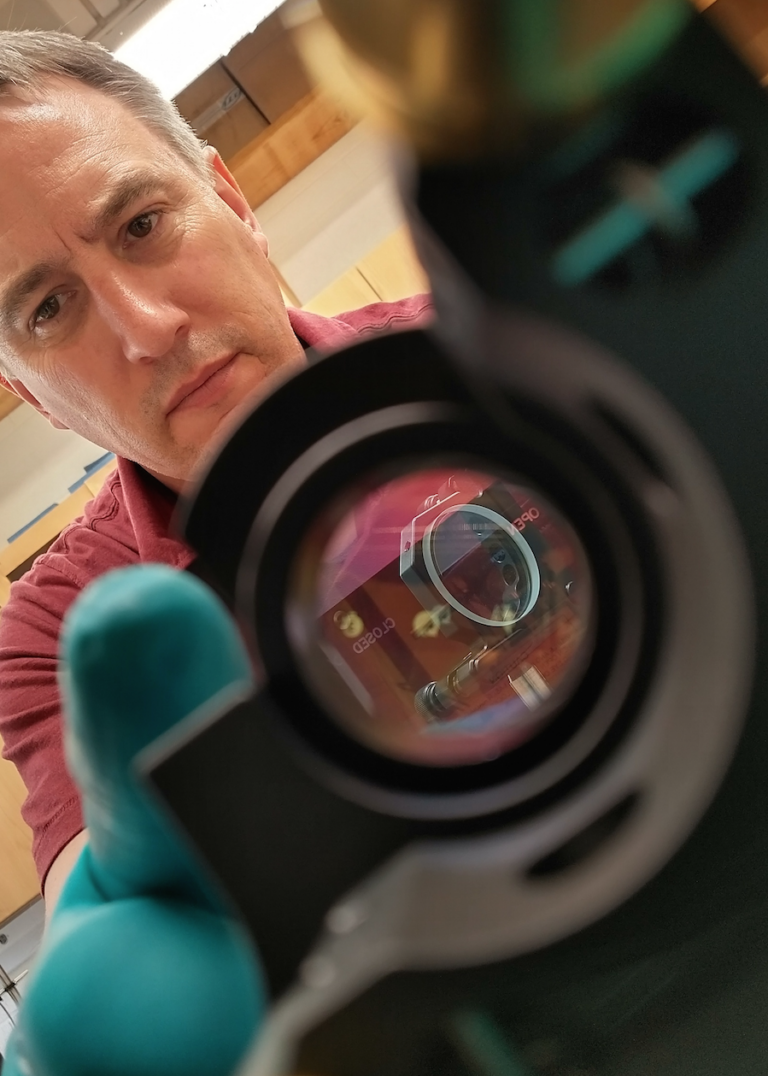

With NASA support, device for future lunar mission being developed at WashU

Scientists at WashU are developing a prototype for an instrument for a future Moon mission with support from a nearly $3 million grant from NASA.

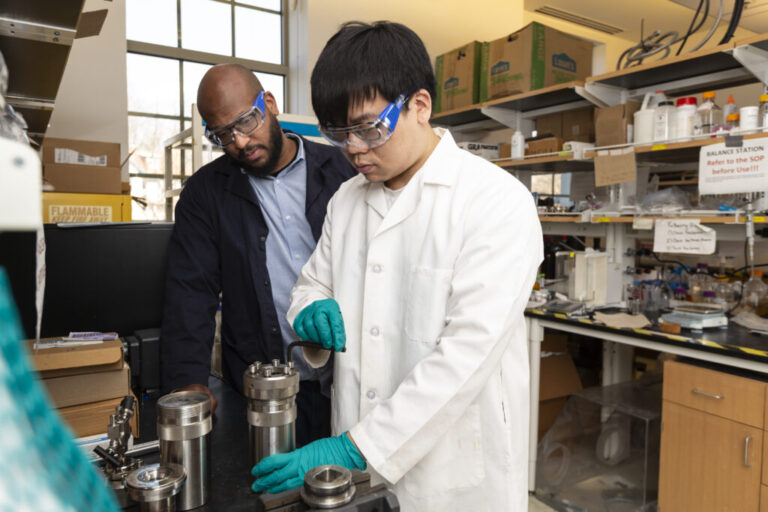

Efficient lithium-air battery under development to speed electrification of transit

Xianglin Li leads team with $1.5 million from ARPA-E for next-generation, high-energy battery

The WashU ecosystem

Within the WashU ecosystem of environmental research, education, and practice, the Center for the Environment serves as a connector. Much like a biodiversity corridor, we work to create space where our partners within the ecosystem and across distinct disciplines come together to address our world’s biggest environmental challenges.

In the news

Connect with us

Upcoming Events